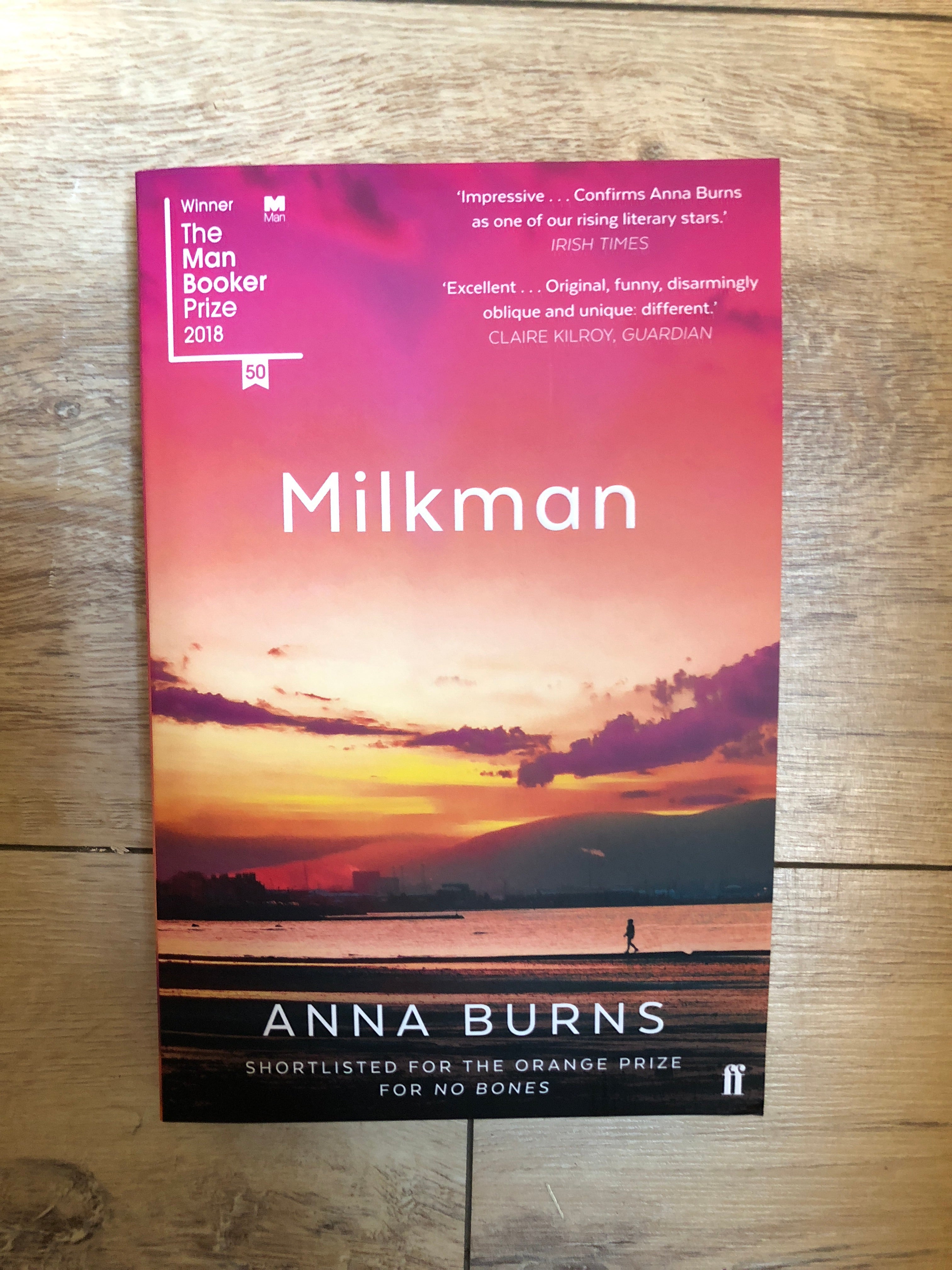

What’s extraordinary about all this, though easy to overlook on a first reading, at least until the final stretch, is the density and tightness of the plotting behind the narrator’s apparently rambling performance. It’s a brilliant rhetorical balancing act, and the narrator can be very funny. On the other, the narrator’s mad, first-principles language, with its abundance of phrases in inverted commas and sudden changes of register, is also used to describe the inner world of a young woman. it’s clearly part of Burns’s project in Milkman to redescribe the Troubles without using such terms as ‘the Troubles’, ‘Britain’ and ‘Ireland’, ‘Protestant’ and ‘Catholic’, ‘RUC’ and ‘British army’ and ‘IRA’. You just have to turn your face toward it, and give it your full attention. For all the darkness of the world it illuminates, Milkman is as strange and variegated and brilliant as a northern sunset. There is a pulsating menace at the heart of the book, of which the title character is an uncannily indeterminate avatar, but also a deep sadness at the human cost of conflict.

But it also seems clear to me that these insistent strategies are in service of the book’s mood of total claustrophobia, and that they contribute to, rather than diminish, its overall effectiveness. The book’s long sentences, its penchant for the exhaustive, can at times be challenging, and there were stretches where I found its uncanny energies stagnated for too long. Among Burns’ singular strengths as a writer is her ability to address the topics of trauma and tyranny with a playfulness that somehow never diminishes the sense of her absolute seriousness. For all the simplicity of its setup, Milkman is a richly complex portrayal of a besieged community and its traumatized citizens, of lives lived within many concentric circles of oppression.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)